- Home

- Derek Hough

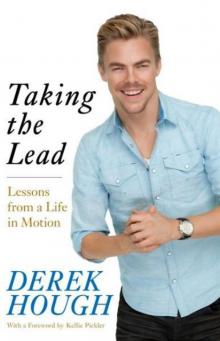

Taking the Lead: Lessons From a Life in Motion Page 2

Taking the Lead: Lessons From a Life in Motion Read online

Page 2

Because I was the only boy, I was the only one who had his own room. It was at the top of the stairs to the left, right next to my parents’ room (I suppose they put me there to keep an eye on me). My four sisters had to share two rooms to the right, while I got my own space with two single beds. Sometimes I’d get up in the middle of the night and switch beds just for fun. I could open my window and climb out on the first-story roof and lie there, gazing up at the night sky. In Boy Scouts, I learned about constellations, so I’d try to spot the Big Dipper, Cassiopeia, the Pleiades or Seven Sisters. They seemed so far away, yet I could close one eye and balance them on the tips of my fingers.

I covered the walls of my room with pictures of tigers. I was obsessed with these beautiful, ferocious animals. My dad hoarded hundreds of National Geographic magazines, so one day I went through his stacks and cut out all the tiger photos I could find to make a giant collage. I don’t think he was too thrilled that I tore up his collection, but he understood my passion. Tigers fascinated me for so many reasons. They’re strong and fierce, but also beautiful and elegant. I remember loving the way they moved, how they were able to control their power. I would spend hours staring at their faces and drawing them: the eyes could display such a range of emotion. I loved that they have no fear. When they walk through a jungle, they own it.

Maybe I wasn’t the most “normal” kid, but in our home, we were taught to embrace individuality and creativity. I felt like we didn’t have a lot of toys, and for a long time I assumed we were poor. But that really wasn’t the case. We could have afforded anything that the rest of the kids in our neighborhood had. My mom just thought it would be better if we used our imaginations and our hands to create things rather than buy them. I remember how badly I wanted a sword to play with. My mother handed me a piece of paper. “Draw it,” she said.

So I did. I sketched out every detail, from the curve of the blade to the shiny silver handle. We had this carpenter’s saw we kept in the basement, so my mom could actually cut shapes out of wood. Together, we worked to bring that sword to life. I even covered it with glow-in-the-dark paint. I thought it was pretty awesome, till I went to my friend’s house and he had the Nerf 3000 thunderbolt lightning super-duper state-of-the-art lights, bells, and buzzers sword—or whatever it was called. That thing was insane! Embarrassed, I hid my makeshift sword behind my back. But looking back, I can see now the value of what my parents were trying to teach us. They were giving us the power to create, the power to see something in your mind and make it real. The lesson was probably lost on a six-year-old, but it did stick with me. Now I’m kind of like MacGyver when something needs to get done.

The Houghs were different, that’s for sure, but I was never embarrassed by that fact. I was glad to be on that side of the fence. South Jordan, Utah, where we settled, was a tight community. Everyone knew everyone, and everyone knew everyone’s business. We lived in a big gray house, the last one in a cul-de-sac, perched on top of a hill. We had maybe an acre of land, mostly trees, surrounding us. I would sit out in the backyard, looking out from the top of that hill, pretending I was Indiana Jones. The mountains in the distance held the promise of adventure and danger. One group of trees formed the shape of a spade, and—like a secret spot on a treasure map—I was confident that a Temple of Doom was buried there. One day, I told myself, I’d hike out there with my backpack and hat and discover it. I wanted to be in the center of danger, to go places people had never gone before. For a scrawny little kid, I had a lot of guts—either that or stupidity.

In the meantime, I had my backyard to tide me over. I would crawl on my stomach through the mud and the dirt. I’d dig trenches and build forts and wield my sword and whip as I made my way through the dark and dangerous forest filled with snakes and ancient curses. As I got a little older, I realized archeology wasn’t as cool as the Indy movies made it out to be. I’d have to go to college and study a lot of boring history instead of tracking down the Lost Ark. So I abandoned that career goal. But I’m still an adventure junkie. I feel so alive when I’m on the edge—always have, always will.

Though I loved danger, I preferred to choose it myself, not have it thrust upon me. We had these neighbors down the road who clearly had something against us, although I couldn’t tell you why. Their sons were big kids who were several years older than I was—and it felt like they made it their mission to torture and torment my family. If I close my eyes today, I can’t see their faces; I think I blocked them out. But what I do recall vividly are feelings—how the hair on the back of my neck stood on edge whenever they came around. I remember the fear and the anxiety. I never quite knew how far they’d go or what they were capable of, so I assumed the worst. I assumed that one day, whether on purpose or by accident, they would kill me.

I wasn’t that far off. Taunts and teasing and dares of “Go ahead, make me!” quickly turned physical. One of the brothers ripped my sister Sharee’s earrings out of her ears, severing her lobes. She came running home with blood pouring down her neck. My mother went over to their house and went ballistic. I had never heard her scream like that before, and I probably never will again. She was a mama bear protecting her young. They insisted it was “an accident” and their mother went along with it. They were playing a game and threw a blanket over Sharee’s head and snatched it away; the earrings simply caught in the fabric. But my mother made it pretty clear that they’d better stay far away from any of us or she’d take matters into her own hands (and it wouldn’t be “an accident.”).

Of course, this didn’t stop them. One day, shortly after, it was my turn. I was about six years old, playing on a trampoline in a friend’s backyard. The brothers strolled up to us and asked if we wanted to play guns. I didn’t like the sound of that and hesitated, but my friend wanted to join in the fun. Before I could say anything more, the brothers dragged me off the trampoline and threw me down on the ground. One of them sat on top of me while the other tied a rope tightly around my ankles. My friend went along with it—or he was too scared to try to stop them. The ropes dug into my skin. I couldn’t wriggle out of them; the knots were so tight, they cut off the circulation, and all I could feel were pins and needles in my toes. They dragged me facedown on the ground. I must have hit my head, because I tasted blood in my mouth.

They threw the other side of the rope over a thick tree branch and pulled it until I was suspended upside down by my ankles about six feet in the air. I remember feeling cold—it was dusk and there was an early autumn breeze in the air. I’m not sure how long I was in this position, only that the sun eventually set and it became pitch dark and bone-chillingly cold. I thought my head was going to explode from the blood rushing to it—or that some wild animal would discover me in the darkness and pick the flesh off my bones.

“Let me go!” I screamed. As I hung there, helpless and terrified, they spit in my face, over and over again. Then they held a pistol to my head and threatened to pull the trigger. “Shut up or we’ll shoot.” I knew the family hunted, so I wasn’t 100 percent sure it was a toy gun. I thought I was going to die; they would leave me there to rot and freeze to death. My mom and dad or my sisters would find my body in the morning. So I screamed. I cried. I pleaded. I begged. Eventually—because I think they got tired of me carrying on—they let me down. My head was throbbing and I couldn’t feel my feet. I was so cold, my teeth were chattering. I stumbled home as fast as I could, ran upstairs to my bedroom, and hid under the covers. I didn’t tell anyone. I was afraid if I told, my parents would want to keep me safe, and they’d never allow me to go back out and play with my friends again. So I never told a soul.

But often, in the middle of the night, I’d wake up screaming from a nightmare. I’d dream that the brothers had strung me up again—or they were following me, guns in hand, planning their next ambush. It was the first time in my life I felt real fear, real danger. Not the kind of fear a little kid experiences when he thinks the bogeyman is lurking under his bed at night, but real fear that sh

akes you to your core because it’s so real and so close—in my case, three houses away.

The day after the gun incident, we all went to church and I saw our neighbors there, blessing the sacrament. I was confused and angry. Didn’t God see what they did to me? Didn’t he care? I knew what my dad would say: “God knows and sees all. It’s in his hands.” But that didn’t make me feel any better or less frightened that the brothers could get away with this and there would be no punishment. Looking back, it was probably the first time I questioned my faith. We ended up moving about three miles away a few years later, largely because of this family.

At my new school, Monte Vista, I was awkward and had a hard time making friends and trusting people. I struggled in class. Facts and figures didn’t interest me. What can I say? We all learn things differently. Einstein had this theory that everyone is a genius, but if you have a classroom filled with different animals—say, a tiger, a monkey, and a fish in a bowl—and you ask them all to climb a tree, the fish is going to feel dumb because he can’t climb those branches. I was the fish. But each person has their own genius and their own skill; just because you don’t pass the test, it doesn’t mean you’re dumb. My teachers, though, constantly told me that I wasn’t very smart, and after a while, I started to believe them.

Recess was the time to prove yourself. We’d play football, and because I was the runt and the new kid, I was always the last kid picked. But I’d make a very conscious decision to intercept the ball so all the cool kids would see me and notice me. Eventually, I went from being last pick to first pick. For the first time, I felt my value and my worth on a team. I had something to contribute.

Yet I never felt like I belonged at school. No one got me or shared my creativity. I was labeled “weird,” so that’s how I felt. No matter how I tried to act, dress, even swear like everyone else, I stuck out. Then one day, my mom dragged me to my sisters’ dance classes at Center Stage Studio in Orem, Utah. My mom was always my biggest supporter, but truthfully, this was also a case of making her life easier. If all the Hough kids could go to the same after-school activity, it meant less running around for her. And Center Stage was delighted to have us all—they thought they had found themselves the blond Osmonds! When I finally stopped complaining, I realized this place was pretty magical. Everyone was so positive, so full of passion and energy. I learned a valuable lesson: You are who you hang around with.

From day 1, I had a natural rhythm and musicality. I went from the kid classes into the adult ones in a matter of weeks. I’m not sure where it came from—maybe the drum lessons my parents gave me. What I lacked in discipline and technique, I made up for with exuberance. I could actually feel the song rising up through my body. I could bring it to life through movement. I could express every emotion I was feeling: fear, pain, anger, frustration, loneliness, excitement. It exploded out of me. And truth be told, I was into girls, and the dance studio was filled with them.

So the kid who pitched a fit about going to dance class suddenly became a regular. Flying around the room, leaping through the air, I felt there was nothing—and no one—that could hold me down.

LEADING LESSONS

For a kid who never liked to pick apart a math equation, I have a pretty analytical brain. A few years ago, I came to the conclusion that you have to be an active participant in your life. You have to stop, take stock, and put things in perspective so you can see the bigger picture. I can’t tell you the exact moment this truth dawned on me; there was no single earth-shattering event or catalyst. But I do remember being at a U2 concert with my sister and tearing up as all these memories of my childhood and listening to U2 flooded over me. It took me back to a time of family and fun and feeling connected. A few weeks later, I was sitting at home in my apartment, looking at my collection of trophies and thinking, Yeah? So? Now what? Winning—the one thing that used to mean the world to me—felt empty. It didn’t matter how much hardware I accumulated, it didn’t give me that adrenaline high anymore.

What did was the feeling of connecting with people. Not just my dance partners, but strangers who would come up to me on the street and share their stories. There have been many who cornered me in a parking lot or sent me a message on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter. Too many to count, but one in particular stands out. A woman stopped me on the street to tell me about her grandmother. “She loved you,” she said. “She watched you from her hospital bed every night Dancing with the Stars was on. You took her back to a time when she loved to dance. You gave her such joy in her final days.” I got a lump in my throat. I had done this for someone? I thanked her and she took my hand. “No. Thank you.” It felt great. More than that, it felt right. It planted a seed in me, which I can honestly say was the beginning of this book.

Not too long ago, I agreed to give a twenty-minute lecture about health and dance, and it turned into two hours. Again, I felt that high from connecting with the audience, from sharing what I had learned. I began to look at my experiences as life lessons. What could they teach me? What was the purpose of my pain and suffering if not to make me a better, stronger person who is more equipped to lead? You know the old saying “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” I think it’s more than that. I think what doesn’t kill you makes you wiser and a better human being. It opens your eyes, your heart, and your mind. You may not have control over everything that happens to you in your life externally, but you always have some control over what’s going on internally—how you handle your life experiences and what you take away from them.

In each chapter, I want to share with you the lessons I’ve learned. And if I make you pause for a moment and consider your own experiences as stepping-stones to taking the lead in your life, then I’ve done my job. I never imagined myself as a teacher—I was the worst student in school, the one you would vote most likely not to succeed. But now, I want to continue to learn more about myself and about human behavior. We all have God-given talent. The question is, what are you going to do with it?

I went to see the musical Pippin on Broadway with my Season 10 DWTS partner, Nicole Scherzinger. There’s this great line in the song “Corner of the Sky”: “Don’t you see I want my life to be something more than long?” I can relate. I want to leave my footprint on this world in a positive, meaningful way. I want to lead by example. To do that takes a lot of introspection. It also takes courage. I try and see it as connecting the dots—the way I used to try and spot the constellations from my rooftop by drawing imaginary lines between the stars. Every moment in your life should be meaningful; each one should have a takeaway lesson. At the end of every chapter, you’ll find mine.

Speak up.

Bullying can be physical, verbal, or emotional—words and threats are just as painful as fists. I know now that the worst thing you can do is suffer in silence. The bullies are counting on you to keep your mouth shut. By doing so, you’re giving them even more power. I understand the desire to leave it outside your front door, to just pretend the bullying doesn’t happen. In my case, I kept quiet because I was certain that tattling would make my situation worse. Either the brothers would kill me for telling, or my parents would confine me to my house to protect me from all things evil. I was convinced it was a lose-lose situation. But I realize now that I was wrong, and if I could go back and talk to my six-year-old self I would tell him to trust someone and get help—from a parent, an older sibling, a teacher. You’re not a wimp if you tell. In fact, seeking help requires incredible strength and courage. The most powerful weapon you have is your voice.

Nowadays, it’s easy to bully by hiding behind a phone or a computer screen. The words that people express on Facebook, Instagram, whatever—they’re just as cutting and painful as a physical blow. I discovered this when I entered the public eye. Social media has become a playground for cowardly, insecure individuals who unfortunately feel the need to direct negative comments and energy at someone they don’t even know. At first I reacted to it. Every obnoxious remark used to dwell in my

mind. But the more I learned about human behavior, the clearer it became that the negativity these people project is a reflection of who they are. I don’t believe it makes them bad people, but they are seeking a significance that they are not getting elsewhere. Realizing this makes it much easier for me to ignore the haters and not take the bait.

Power over others is weakness in disguise.

People talk a lot about how bullying can destroy your life. For me, it’s been a revelation. I got hit in the head a lot of times in my childhood, so maybe it finally knocked some sense into me. I understand now that someone who is strong and loves himself would only ever give love back. The superior human being will always see the light in someone and choose to encourage that light instead of dimming it. Those brothers? They needed to control me because they wanted to feel important. They craved attention and resorted to violence to get it. They needed to control me because they were weak. Looking back now, I actually feel sorry for them. I don’t feel like the victim anymore; I was a witness to their suffering. It’s helped me move past the pain and fear and make peace with this part of my past. Kids tend to blame themselves when they’re bullied—as if something they have done is causing some mean kid to beat the crap out of them. But I see now it was never about me. I did nothing to these brothers. I didn’t provoke them; I didn’t ask for trouble. They simply saw an easy prey. I ask myself over and over what must have been going on in their heads to make them unleash such wrath on me and my family? What kind of personal pain or insecurity was behind it? Trying to understand helps me let go of the anger and begin to forgive.

Taking the Lead: Lessons From a Life in Motion

Taking the Lead: Lessons From a Life in Motion